On the afternoon of November 13, Mike Siravo was standing outside his family’s landscaping business in Northeast Philadelphia, dressed in khakis and a company polo shirt, watching as strangers pulled up in nice cars, parked without care on the busy street, and approached the barbed-wire-topped fence with iPhones gripped in outstretched hands. They all came for the same reason: to see for themselves the words FOUR SEASONS TOTAL LANDSCAPING. SINCE 1992. PARKING ONLY. ALL OTHERS WILL BE TOWED AT OWNERS’ EXPENSE. In packs, they laughed openly. Alone, they wore bemused expressions, eyes focused on their screens. All of them spent a few minutes taking in the sight and, more importantly, documenting their visit with selfies.

Workers walked in and out of the parking lot, sometimes shaking their heads but mostly keeping them down and not saying much to any of the outsiders for whom the landscaping company was now an unusual monument to the end of America, or the end of the thing that had symbolized the end of America, or something. It was three o’clock on a workday. “I’m just an employee,” one of them said. “I don’t know anything.”

A man on a bicycle paused near the front office to stare at the building. On the other side of the blinds, there were desks and filing cabinets illuminated by fluorescent light and people going about their day, which would have been a normal one were it not for the 20,000 T-shirt orders to process and the intrusion of tourists who saw the place as some kind of zoo exhibition. There was an awkward silence, but then Siravo smiled and shrugged in the direction of the sidewalk, asking the curious bicyclist the obvious question: Was he looking for a photo? He leapt down the steps to take the man’s phone and, with the enthusiasm of a mall photographer, instructed him how to pose. Siravo leaned back into the street, making sure the angle captured the green-and-white awning with the company name.

A couple of feet away, a family of four was staging a holiday card. Lois Neuberger and Matthew Gold said they were in town from California, visiting their daughter at school, when it occurred to them they were just a short distance from the festive greeting–slash–political meme of a lifetime. “It’s become such a thing that we decided it would be a fun idea,” Gold said with a laugh. “Everyone will get it.” (Including me, in the literal sense, since the Neuberger-Golds kindly added my address to their mailing list.)

By then, there were all sorts of rumors on State Road about the Siravo family’s connections with the Trump campaign and the Philadelphia Republican Party. But it had been nearly a week since Rudy Giuliani’s press conference in the parking lot out back, and the only evidence anyone could turn up to support the theory that what had occurred here wasn’t just a freak public-relations accident or hilarious fuckup were a few pro-Trump Facebook posts from Mike’s mother, Marie Siravo, who owns the business. She had been shrewd enough to release a statement amid the frenzy that said the landscapers were not partisans and then to mostly avoid speaking to the media as she rushed out the door, clutching a Louis Vuitton bag, to a white Jeep with a FOUR SEASONS license plate on the front bumper. The Siravos were nothing if not good marketers, and by December, they’d sold more than $1 million of the merchandise they’d drawn up to capitalize on all the attention, like stickers that read “Make America Rake Again!” and “Lawn and Order!”

“We don’t really know how it happened. We heard it might’ve been a mistake or something,” Mike Siravo said. “We just kinda picked up the phone and said yes and cleared some stuff out and managed to make it happen.”

If that was true, it didn’t explain how it came to be that the phone rang at Four Seasons Total Landscaping in the first place. Siravo wouldn’t say who had called, or if he knew how Donald Trump’s campaign had even heard of the small landscaping business, or anything else, really, that might tell how this stretch of asphalt became the official site of the end of the presidency and the beginning of the ass-backward pseudo-legal effort to reverse the results of the election. According to the New York Times, there had been a miscommunication between Trump and the event planners. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the campaign made the staging choice that morning, after calling one of the Siravo’s employees. My search for answers involved — I swear to God — more than 37 sources spread throughout the White House, the Trump campaign, the president’s network of advisers both formal and informal, the Republican Party, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

This is not counting Siravo, who said he was sorry, but his family had decided not to talk — except, he added, about golf. They’d just done an interview limited to the subject of Four Seasons Total Landscaping’s approach to manicuring courses.

The sound of Donald Trump’s voice was unmistakable. It boomed through Rudy Giuliani’s phone and traveled across the hall where anyone could hear that the president was on the line and — this was unmistakable, too — he was unhappy.

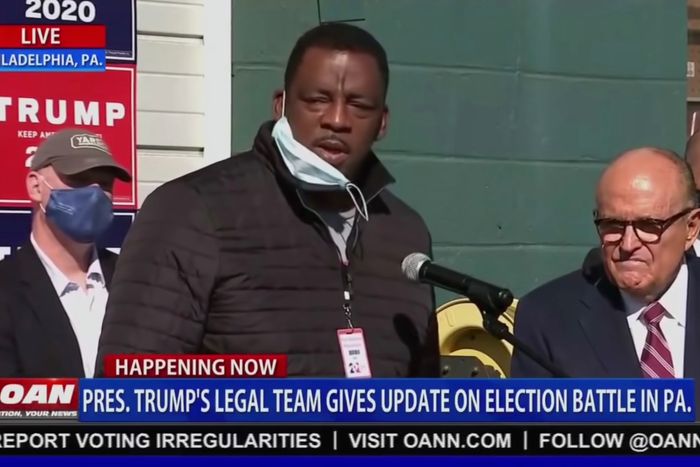

“I’m like, ‘Oh damn, it’s the president on the phone!’” Daryl Brooks said. “I know what his voice sounds like — and he sounded pissed.”

It was November 7, and the president — on the verge of Electoral College defeat, with the whole country glued to cable news, where manic nerds gestured frantically at maps and related esoteric trivia about swing-state counties that few non-locals had heard of — had been pissed for four consecutive days.

People close to Trump often issue reports about his mood, and his mood is often sour, but multiple White House officials told me things were so volatile after Election Day that they were outright avoiding the president out of concern he might end up using any nearby staffer as a human stress ball. (The personal benefits of proximity, which would ordinarily outweigh the drawbacks of verbal abuse, waned alongside Trump’s election chances.) “It’s been so bad,” a senior White House official said. On Election Night, this person said, they walked into the residence, saw the president screaming, then turned around and walked right back out.

But there is a thin line between bitterness and optimism, and as he prepared to depart the White House for his golf course in Sterling, Virginia, for the 299th time during his presidency, Trump fired off a few tweets to allege, without evidence, that the election was being stolen. What came next barely registered — at first. Later that morning, he tweeted, his lawyers would be holding a press conference at “Four Seasons, Philadelphia.”

As he waited for the event to start on that Saturday morning, Daryl Brooks, a Republican poll watcher and frequent third-party candidate in New Jersey, was so excited to hear the president’s familiar rasp and glimpse his famous attorney that he didn’t really pause to consider what the source of the conflict might be. And he didn’t think it was strange that he’d been asked to take part in a press conference on so little notice, or that he wasn’t even sure where, exactly, he was. Brooks said he received a call that morning from James Baehr, a lawyer who serves in the White House as the special assistant to the president for domestic affairs (where he earns a government salary of $135,000, according to public records). Baehr told Brooks to meet him at the Hampton Inn near the Convention Center, and from there, he was driven to the location, where he entered through the side without catching sight of any identifying markers. “It looked like a construction or landscaping company or something,” Brooks said. (Asked for comment, a White House spokesperson said, “After consultation with White House counsel and his supervisor, James took personal leave for a few days after the election to assist in Philadelphia.”)

Several campaign officials said the president’s tweet was the first they had heard about any event planned for the day but that, given the president’s nature, nothing about this seemed out of the ordinary. Scheduling surprises had been Trump’s style from the earliest days of his first campaign, after all, and no half-conscious person who worked for him for longer than a day could maintain the belief that the operation would ever achieve or even aspire to orderliness. (“Formal isn’t a word I would use to describe anything we do,” as one diplomatic staffer put it.) The advertised location did not stick out as unusual, either. Hotels are often booked to hold political and media conferences of all kinds, equipped as they are with vast ballrooms and efficient hospitality workers on hand to unstack rows of cushioned dining chairs on fields of carpet between the American flags and the swarms of reporters.

And since there’s no Trump International Hotel in Philly yet, a Four Seasons would certainly do. With a name that suggests marble floors and gilded lighting fixtures and other trappings of luxury to which his own brand yearns, it would surely please the president more than a Marriott or a Holiday Inn. Plus, more practically, a hive of post-election activity was a few blocks away at the Convention Center, where absentee ballots were being counted and where campaign officials had staged an impromptu press event two days before. (That’s where Brooks had first met Pam Bondi and Corey Lewandowski, which was exciting, too, even if he didn’t really seem to know who they were. On Facebook, he posted selfies with them, identifying Bondi as “from Fox News” and calling Lewandowski “Cory Lewendowske” repeatedly.) “I thought, Okay, nice hotel,” a senior campaign official said.

But the campaign had made no attempt to book the nice hotel for the press conference. Instead, according to a second official, the event was supposed to take place at the Union League of Philadelphia, a historic club founded in 1862 in support of Abraham Lincoln. The president claims to admire Lincoln — though mostly he seems to enjoy talking about how Lincoln was also a Republican and, despite a rather famous cranial encounter with a bullet, how people were more fair to Lincoln than they are to him — so this made a certain amount of thematic sense.

The official thought the venue had canceled on the campaign owing to the health department’s COVID restrictions, which prevent gatherings of more than 25 people, but attempts to confirm this with the Union League were unsuccessful, since the only person I could get to talk over there was a nice man in the security office who had no information to share other than the fact that, to his knowledge, no events of any kind were happening during the pandemic.

A third official said that the press conference was first supposed to take place at the United Republican Club, but Frank Cristinzio, its treasurer, said that they’ve been closed for months and had not discussed hosting an event with the campaign or any associated attorneys. “Maybe they thought about it,” he said, “but I didn’t hear about it.” In fact, Cristinzio said, things at the club were so dead nowadays that the only reason he was even there to answer the phone when I happened to call was because he had to stop by every now and then to check the mail.

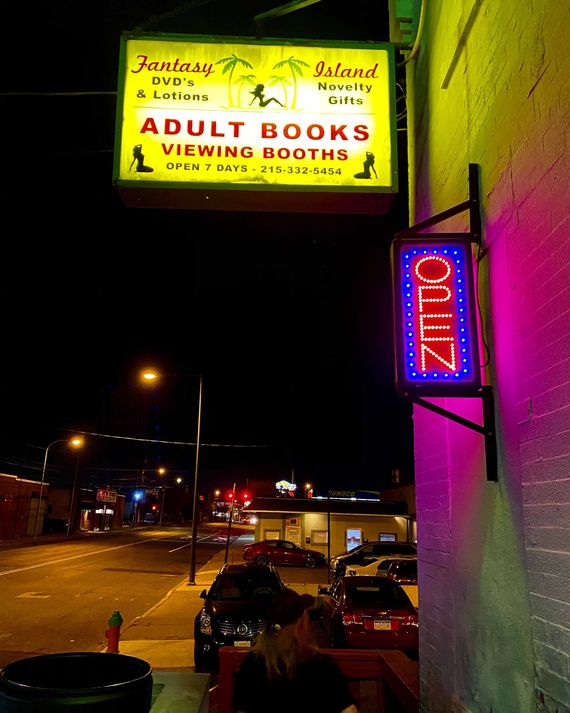

Trump followed up his announcement with a second announcement. Rather than the Four Seasons hotel, the press conference would be held at Four Seasons Total Landscaping — on State Road, in an industrial patch of Northeast Philadelphia, near an interstate and a few doors down from the Fantasy Island Adult Book Store and across the street from a crematorium. If you hit the Pentecostal church, you’ve gone too far.

“Four Season’s Landscaping!” the president said (apostrophe his). “Big press conference today in Philadelphia at Four Seasons Total Landscaping — 11:30am!” A few minutes later, he left the White House in “shoes that look[ed] appropriate for golfing” and a white “Make America Great Again” hat, according to the photographer on the scene, and boarded his motorcade. “Lawyer’s Press Conference at Four Season’s Landscaping, Philadelphia,” he said in another tweet. “Enjoy!”

It’s hard to know what counts as a fuckup when you work for Donald Trump. Looked at by the standards of a traditional campaign with a traditional candidate who possesses a minor-to-moderate capacity for traditional human feelings, like shame, what happened at Four Seasons Total Landscaping, or the fact that it happened at all, was a disaster. A press conference is supposed to convince the public of whatever case you’re making through the act of being — or more likely pretending to be —transparent. That is, obviously, not what happened on the blacktop. But looked at in terms of attention generated and relevance sustained, two other goals of a press conference, the thing was a clear success. Plus it was the rare political joke that appealed to everyone.

“Out of all the things that have happened, this was the funniest thing, and it came at the last minute,” Tim Heidecker said. A comedian and songwriter who used to live in Philadelphia, Heidecker said that if he had tried to write the scene as fiction, he was sure the reaction would be, “‘Naawww, that’s too hokey!’” As a comedy event, Four Seasons Total Landscaping was “not as sophisticated as I would usually like,” Heidecker said, but it worked perfectly because it was “simple and clean,” just “a basic comedy concept,” but organically staged in the wild. He was inspired by what he saw on the news that morning, and he felt called to put it to music. “I always start with the first line, and it seemed perfect that Rudy Giuliani was standing very literally surrounded by manure,” he said. The song is called “Rudy at the 4 Seasons,” and it starts there, rhyming manure with “spitting out lies that belong in the sewer.”

In setting and content, the event served for some campaign officials and presidential advisers as a representation of the brokenness of Trumpworld. If it was an advance failure, well, people familiar with the inner workings of the campaign said they could’ve seen that coming. “When you hear ‘a friendly local business that’s supportive,’ that sounds great,” a senior official said. “But when you dig into the details on the ground, things are a little different.” A proper advance team, for instance, would have gone to scope things out before securing the location, taking note of nearby landmarks like the porn shop and the crematorium. “The tight shot was good, the message was delivered, but unfortunately —” the official said, trailing off.

It’s not that anyone would venture to argue that things had ever run smoothly on the Trump campaign. But more than most principles, the value of good stagecraft was grasped by the candidate, and he cared enough to know who was behind the mechanics of his public-facing events. His first advance man, George Gigicos, became famous-for-politics, which doesn’t happen much with functionaries unless they start going on TV, which Gigicos never did, or they get indicted, which he managed not to do. Gigicos, who no longer works for Trump, started laughing hysterically when I told him why I was calling. The words four seasons or landscaping now elicit such a reaction from people across the ideological spectrum. “Honest to God, I have no idea how that came about,” he said. “From what I understand, I don’t think the campaign or the White House planned that thing. I think it was the campaign on the ground in Pennsylvania.”

For some officials, there was irony in Brad Parscale’s being fired as the campaign manager following an optics (and public-health) crisis at a MAGA rally. Of all the things Parscale could reasonably be accused of, ignoring the advance team or dismissing the idea that public events were important was not one of them, even if knowing, intellectually, their value did not necessarily translate to knowing how to run a professional operation. “Brad understood. He saw through the president’s eyes what we did and why it mattered,” the senior official said.

Parscale’s replacement, Bill Stepien, had gotten his start doing the thankless logistical chores that make a campaign run, even once working as a driver for his candidate. But by the time he was put in charge of the Trump campaign, time and money were running out, and he was unlikely to engineer an epic reversal of luck by focusing on stunts or by trying to fix the few things, like the president’s airport-hangar-rally programming, that were semi-functioning. “It was different under Stepien,” the official said. “The value of an events schedule, of an advance team, was not at the forefront of his mind, especially during COVID.” Why would it be?

Two senior campaign officials said they assumed the president would want to hold events right after Election Day, and they tried to formalize a process to carry those events out quickly and professionally “on a moment’s notice.” Advance was always being called “at the 11th hour,” even when its members weren’t being outright “ignored,” as they felt was the case under Stepien. So the idea was to prepare with spontaneity in mind, to keep state advance teams on the payroll, ready to go on the ground in the places most likely to be the scenes of post-election legal battles, like Michigan, Georgia, Arizona, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. “The response we were getting back was the same everybody was getting back: ‘We’re not sure what’s happening, and we’re taking it as it comes,’” the official said. The second official put it this way: “They didn’t think that was necessary,” the official said, “and they kinda just scoffed at me.” When the morning of the Four Seasons Total Landscaping event came, several advance staffers had already left the campaign.

But for many people on the campaign and in the White House, there was a more obvious issue threatening the president’s play for an electoral miracle. In the weeks leading up to that Saturday morning, advisers to Trump believed Rudy Giuliani was becoming more and more of a problem. He’d always been a problem, it was true, prone to butt-dialing reporters, or showing up on TV all out of sorts to divulge something at odds with what the president had already claimed to be true, or otherwise catching the attention of hostile foreign governments or domestic investigators or celebrity pranksters.

But in the final sprint to Election Day, managing the known unknowns of Giuliani’s endless capacity to fuck up so much that he was often at the center of several personal and international legal dramas at once was consuming time and manpower at campaign headquarters when there was little left to spare. “We were spending hours each day trying to prevent Rudy from creating a disaster,” a senior campaign official said. “Hours and hours.”

People who were supposed to be focused on winning a presidential race were instead focused on devising ways to distract the once celebrated mayor of New York City. In the office he was a nuisance, but out of sight he was a terror. To keep him busy but accounted for, he was sent on the road as a surrogate, including for a last-minute event in Philadelphia on Columbus Day to launch an otherwise basically fake initiative called Italian Americans for Trump. It was, a second official said, “nightmarish.”

Yet, as loserdom neared, what looked to everyone else like the Rudy Problem looked to Trump like a potential solution. “His style is to keep pounding his head on the door, ultimately believing it will open,” one of his legal advisers told me. “And unfortunately, it has worked several times for him, so you can’t disabuse him of the notion of his persistence.”

“The president’s narcissism cripples him in these moments,” the adviser added, “because as long as people are telling him what they think he wants to hear, it’s a struggle for him to abandon hope. He’s just such a curiously wounded narcissist. If Rudy tells him, ‘We’re gonna destroy all the norms and burn it down and make sure you get reinstated, the president goes, ‘Great!’” The truth, the adviser said, took longer for him to process, and it required whoever uttered it to approach Trump as if he were a wild animal. “When people would bring him bad news, he would blow up, and they would sort of back out of the room.” The trick, the adviser said, is “don’t hit him immediately with something he can react emotionally to” and “don’t appear intimidated.”

A second person familiar with the legal team said Giuliani was put in charge because “the president wanted a peer and a fighter. He wanted somebody that he can relate to.” This person described competing power centers, with the litigators and other serious people on the one side, who realized almost immediately that the president had no legitimate pathway to change the election results, and the conspiracy theorists and crazy people, led by Giuliani, on the other side. The second group won, even after multiple interventions staged by lawyers and family members and other advisers. As usual, Trump was unwilling to let go of the people he perceived to be fighting the hardest for him in public. Which wasn’t a surprise, of course, though it still managed to disappoint the optimists (or idiots, depending on your view) still working for the president with hopes that, after all this time, he might change well-established aspects of his personality.

The person familiar with the legal team never bought the idea, for instance, that Sidney Powell had really been removed as one of the president’s representatives, even though the campaign had put out a statement to that effect. What came out of the president’s mouth, and through his Twitter feed, seemed a reflection of what went into his head via people like Powell, Giuliani, and fellow legal-team member Jenna Ellis. A senior White House official told me that, in the vacuum created by the absence of officials who might try to reason with the president, Trump spent even more time on the phone, dialing up whomever he saw defending him most rabidly on TV. Sometimes, this official said, the White House switchboard operator wouldn’t even know how to contact the person the president wanted to speak to, and this would result in members of the staff being roped in to locate a number for some random pundit from Fox or, increasingly, Newsmax or OANN. As if to prove the leakers’ point, Giuliani, recently recovered from his bout with the coronavirus, visited the White House last week. And according to the New York Times, Powell visited on Friday with the president, who discussed naming her the special counsel on voter fraud.

“There were serious legal challenges that could’ve been mounted, but the show took over,” the person familiar with the legal team said, though if the show took over anything, it was just a different show. “It’s embarrassing for the country, and it’s embarrassing for the president.”

If you’ve ever been involved in politics at any level, you’ve met someone like Daryl Brooks. In New Jersey, where he’s from, he often surfaced around causes and campaigns, earning a reputation as “a wannabe hanger-on,” in the words of a Democrat, and “a self-promoter with no allies,” according to a Republican.

Brooks describes himself as an activist, but it’s more true to say that he’s a man in search of a movement. He first ran for office in 2004 as a member of the Green Party, without success, and then again in 2006 as an independent on a civil-rights and gun-control platform. That was unsuccessful, too. By the Obama era, he was a tea-party libertarian, and by the time Trump was in power, he was a far-right radio host in a tricorn hat, a prop gun in each hand, talking about the “Clinton body count” and Jeffrey Epstein and the “rise in pedophilia.”

A few days before the election, Brooks, who is Black, posted on social media, “Black Americans don’t let Antifa a domestic terrorist group destroy the inner cities Nov 3rd wake up!!!” That day, he said, he’d been paid $100 to work as a poll watcher at the Philadelphia Convention Center. In this sense, Brooks was like many people around the president: He’d spent decades involved in politics in one way or another, but he’d never managed to make his way to the center of anything before he committed to MAGA. “He was basically a kook and a political menace,” Reed Gusciora, the mayor of Trenton, said. “So he fit in really well with Giuliani.”

And then, suddenly, there he was: the first witness called by Giuliani to address the cameras at Four Seasons Total Landscaping. “So, let’s start off first,” Giuliani said, turning stage left and gesturing at Brooks as he walked across the backdrop, a garage door decorated with a checkerboard of blue and red Trump-Pence lawn signs, and met Giuliani with a handshake. He did not appear to know his name. “My friend!” Giuliani said. “Please tell briefly what happened to you, who you are, and what happened to you.”

Brooks complied, describing how poll watchers were kept at a distance from voting booths and prevented from taking photos, which is standard practice at most polling locations on Election Day but which Brooks suggested was fodder for Giuliani’s fraud conspiracy. Giuliani’s grand theory, by the way, was that the election was being stolen through, among other things, ballots cast fraudulently on behalf of dead people — a claim for which there was and is no evidence. As Giuliani spoke that morning, with the president firmly on the golf course, the cable news networks confirmed the mathematically obvious: Biden had won the election.

Brooks told me that he didn’t intend to claim the election was stolen, but if anything, the reaction to his decision to stand alongside Giuliani had only radicalized him more. After the press conference, Politico reported that he had served time more than two decades ago after being convicted of exposing himself to a minor, a crime Brooks still denies committing. He wasn’t sure whether there was fraud at the convention center, he said. And he didn’t know that saying yes to a press conference that morning would mean he would appear aligned with everything that happened there or that he would become a story himself, one that his kids might read. He said that, in his view, what happened in his past did not relate to the current state of the president’s effort to remain in office but that the interest from the press revealed racist motivations. “Nobody’s talking about that Jewish lady there or that Italian lawyer,” he said. (Brooks has already released a book about his experience, titled, 37 Days: The Disenfranchisement of a Philadelphia Poll Worker.)

He wasn’t the only person who attended the press conference and left angry at the media.

“How did I get there?!” Bernie Kerik said with a huff. “How do you think I got there?! I drove!” Kerik, the former New York City police commissioner recently pardoned by President Trump, was not interested in answering questions about his attendance, where he stood behind his friend Rudy, a smirk on his face. “This story is some bullshit story!” he said. Click. I texted Giuliani. “Are you kidding?” he asked me. “My Mom always said anyone can make a mistake. Only an idiot repeats it.”

But even people in Trumpworld had questions.

“Do we know what happened yet?” a senior White House official asked.

“How it happened is still kind of a mystery to me,” a senior campaign official said.

“This is all very us,” another campaign official said. “I’m not shocked or surprised at all.” If luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity, this was the opposite. “That’s how you get the Four Seasons fucking Total Landscaping bullshit.”

Whether it’s war and peace or public relations and gardening, sorting out the truth is a complicated endeavor when it relates to Donald Trump. Everyone involved in anything, no matter the size, no matter how stupid, seems to lie as a first resort, or to know very little, or to lie about knowing very little, or to know just enough to send blame in another direction, and the person in that direction seems to lie also, or to know very little, or to lie about knowing very little, but perhaps they have a theory that sends blame someplace else, and over there, too, you will find more liars, more know-nothings, and before long, a whole month will have passed, and you still haven’t filed your story about how the president’s attorney wound up undermining democracy in a parking lot off I-95 on a strip of cracked pavement in a run-down part of a city that ordinarily would command no consideration from the national political class or the very online public or the equally online mainstream media, which, when forced to look, found lots of reason to laugh.

Bernie D’Angelo didn’t blame them. An electrician by trade and a Rolling Stones fanatic, D’Angelo has owned all kinds of businesses over the years, including a health-food store and a pizza parlor, but Fantasy Island, the adult book store he inherited from his parents, is by far his favorite. He appreciates how it’s “a lot more fun” than the others, generally, and specifically, he appreciates how the adult business strips the airs from anyone who ascends the steps under the bright-yellow sign outside to cross his carpeted threshold. “This is reality,” he said. “When they come in, they check their egos at the door, because look: It is what it is. There’s no sugarcoating it.” He gestured to the wall of dildos on his left.

That Saturday morning, D’Angelo said, he was keeping to himself when a customer ran in to report “a problem going on” outside, where police had suddenly appeared to block off the road. “So we looked out and found it was Giuliani who made a big mistake.” He laughed hard. “He was at the wrong Four Seasons hotel, the wrong one!” He paused to laugh with every few words. “‘Cause that’s a … landscaping! … And not a hotel! … A five-star hotel! … And that’s … one-star … landscaping!” He could barely breathe. “So you’ve got dead people, landscaping, and pornography!”

When I first visited, right after the press conference, the joke was still alive. A local newsman and his camera guy had been set up for a live shot on the sidewalk all afternoon. But soon they were gone. Why wasn’t I? I came back even after I got into a car accident between the landscapers and the Pentecostals (little was damaged beyond my already poor reputation with Avis). After a few days, I wasn’t sure if I truly believed that history had been made in that patch of tar behind Four Seasons Total Landscaping. It was true that the presidency had officially ended there, but it was also true that the site itself felt like someone had erected a somber memorial at the scene of one of the lesbian pillow-fight pornos for sale at Fantasy Island (not that I looked).

About those dead people: Regulations keep crematories out of the way of most businesses, but Delaware Cremation Center would blend in fine in a more developed area, even if the pandemic has made it an unusually busy place. On State Road, it sticks out as weirdly nice-looking. The sign over the doorway is new, the brick façade unweathered. The black shutters around the window compliment an iron bench and gate. If a place where bodies are turned to ash can be welcoming, you could call it that. There’s a space inside for mourners to gather to drink and eat, and there are pews in which to pray. You can see, in these and other small details, how the business of caring for the dead is often about caring for the living. Viewed from here, the Four Seasons Total Landscaping circus looked as much like an indictment of a certain kind of liberalism as an illustration of Trumpian incompetence. But picking at the bones of any joke will make it unfunny after a while, and by the time I was looking at the drawers where they push the bodies in, I’d been trying to make sense of what happened there for too long.

As one Philadelphia Republican official told me: “Duuuuuude! It’s sooooo embarrassing! Oh my God! It’s the height of idiocy!”

It was probably always that simple.

"four" - Google News

December 22, 2020 at 05:05AM

https://ift.tt/3rlollA

The Full(est Possible) Story of the Four Seasons Total Landscaping Press Conference - New York Magazine

"four" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ZSDCx7

https://ift.tt/3fdGID3

No comments:

Post a Comment