The collapse of Enron in 2001 and the demise of its auditor Arthur Andersen not only reduced the Big Five accounting firms to the Big Four but forced most of them to sell their consulting divisions amid a crackdown on conflicts of interest.

In the 20 years that followed, as the Enron fraud faded into history, the groups rebuilt their consulting empires, advising on everything from insolvency to cyber security. But now a fresh stream of scandals has again raised concerns that firms selling services like merger advice cannot also function effectively as auditors.

That has forced Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC to rein in the cross-selling that helped bring them a combined $157bn in annual revenues last year — opening the door for nimble competitors to lure away star performers with generous pay cheques.

Smaller insurgents, many of them private equity-backed, are bidding for the most lucrative divisions of the Big Four’s business without the drag of the low margin, highly regulated and potentially reputation-damaging audit operations.

“We’re not so much stealing their lunch, we’re stealing the food from their cupboard that we want,” said Richard Fleming, head of European restructuring at Alvarez & Marsal, a privately owned company that has hired more than 50 senior advisers from the Big Four in Europe since 2017.

But while the Big Four are already reshaping themselves in response, they are adamant they will defend their turf. Just because they are being raided “doesn’t mean the multidisciplinary model is dead”, said Jon Holt, UK chief executive of KPMG.

Everything but the audit

A Big Four firm with unsettled partners faces a choice similar to a football club negotiating with a “wantaway” player: arrange a quick sale to raise cash and reshape itself, or stand firm and run the risk that its team disintegrates anyway with no financial windfall.

Smaller rivals with ambitious growth plans have found they can turn the heads of Big Four partners who feel underpaid, unloved or constrained from winning clients because of conflicts with the firms’ audit practices.

Both Deloitte and KPMG have been pushed to sell their UK restructuring divisions this year in deals backed by private equity groups CVC Capital Partners and HIG Capital respectively. Other businesses are also being snapped up.

“We are interested in everything but the audit piece,” said one US-based private equity executive who has worked on multiple professional services deals.

The transactions have come thick and fast. PwC’s $2.2bn disposal of its tax and immigration consultancy last month to buyout group Clayton, Dubilier & Rice was by far the Big Four’s largest in recent years.

The group also sold a UK fintech business and parts of its US and Italian advisory divisions to private equity funds; while last year KPMG offloaded its 500-person UK pensions business in a £200m deal.

US-headquartered independent companies such as Alvarez & Marsal, AlixPartners, and FTI Consulting have also been hiring star Big Four practitioners to fuel global expansion.

‘We can recognise people’s achievements . . . ’

Private equity funds and independent players are tempting partners with promises of fewer turf wars, quicker decisions and investment in neglected areas — but the promise of greater riches is also helping.

High performers can keep more of their earnings than in the traditional Big Four model, where length of service is a key factor defining the share of profits.

“Younger partners who are highly talented are getting increasingly impatient about seeing justifiable rewards for what they do,” said Timothy Mahapatra, a managing director at Alvarez & Marsal, adding that the Big Four now make salaried staff wait longer before becoming partners who share in the firm’s profits. “We can recognise people’s achievements more readily.”

The Big Four firms have swollen to employ about 1.2m people worldwide with the resulting bureaucracy leaving some partners feeling disenfranchised.

“Once you’re at 600 partners you’re not really in the equity at that size, you’re really sort of glorified employees,” said Mark Raddan, head of advisory at Interpath Advisory, the restructuring business sold by KPMG to HIG this year.

But in the face of private equity cash, the Big Four are bullish about keeping the majority of their partners, arguing that their model offers stable income from diverse business lines and is suited to helping clients tackle the changes wrought by the pandemic, climate change and Brexit.

“You need a global multidisciplinary firm to answer those problems because it’s not a single line question that they’re asking you,” Holt said.

That means, say executives at the Big Four, that sales are sometimes by choice. “It’s about pruning the portfolio, creating investment capacity to then do other deals to acquire capabilities that we might not have at the moment on the scale [we need] for the future,” said one such global executive.

Sometimes a disposal works for both sides. Andrew Coles, chief executive at Isio, the UK pensions division sold by KPMG, said his firm has expanded faster as an independent business through a recent acquisition. “Could KPMG have written the cheque? Of course they could have. Would they have done it? I’m not sure.”

Levering up

The success of some early buyouts sparked private equity’s interest. CVC roughly quadrupled its money on its stake in AlixPartners between 2012 and 2016, according to two people familiar with the investment.

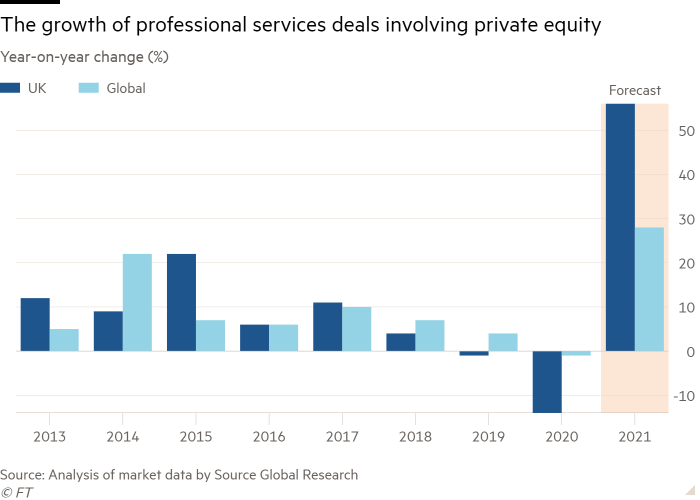

Globally, the number of professional services deals involving private equity groups has grown steadily since 2013, according to analysis by Source Global Research, a data provider to consultants.

In the UK alone, it said market data suggested there were more than 400 deals in 2020, a figure that could increase by more than half this year based on current trends.

Buyout groups also used to avoid buying professional services businesses, in part because banks were wary of extending large amounts of debt to companies whose main assets are people, rather than plant or machinery.

However, lenders have gotten increasingly used to funding private equity to buy up professional firms — and with increasing amounts of leverage — while the firms have learnt how to hold on to star performers, for example with stock options that can be clawed back.

The risks remain real

But buying a business whose assets are people comes with risks. Two founders of Teneo, the CVC-owned public relations and advisory group that bought Deloitte’s restructuring business this year, have left the company in separate reputational crises within months of each other.

There are also commercial risks for the newly spun off entities. Teneo’s $605m in senior debt left it leveraged at more than six times its core earnings as of March this year, according to Moody’s, reducing its room to manoeuvre if things went wrong.

HIG’s acquisition valued Interpath at about £375m, according to people familiar with the terms, prompting some competitors to question whether it can deliver a satisfactory return even if it expands internationally or diversifies into areas such as forensic accounting.

Looming over the recent purchases is the fact that the restructuring industry has been quieter than expected during the pandemic with government support, banks and equity markets all helping businesses to survive.

At the same time, competition is intense: Seven or eight restructuring advisers can pitch for a single job, said one insolvency lawyer.

A consulting group that can charge 73 or 75 per cent of staff time to clients can “make a lot of money” but if this “utilisation” rate falls even a few percentage points, losses can mount quickly, said Fiona Czerniawska, chief executive of Source Global Research.

Without Deloitte and KPMG’s extensive global networks, rivals say the newly independent businesses at Interpath and Teneo might struggle to win big ticket international roles. The pair have their sights set on international expansion but even if they succeed it will take time.

“They might hire someone here or there in a different jurisdiction but within the short to medium term they are far weaker competitors today than they were yesterday,” said Fleming, who led a team of partners from KPMG to Alvarez & Marsal in 2017.

Predator or prey?

Smaller competitors hunting their business has so far failed to halt the Big Four’s growth. Three of the firms have reported increased revenues this year with KPMG’s results due in December.

And Big Four executives are keen to paint raids by private equity as the normal churn of creating and selling new businesses. They are already buying businesses and building internally in areas where they anticipate growth after the pandemic: technology, cloud computing, climate change, instilling cultural change within companies and M&A advice — crucially, they say, by choice rather than necessity.

But for insurgents looking on, those moves do not change the fact that the Big Four are the prey: “I think they’re defenceless,” said Fleming.

"four" - Google News

November 17, 2021 at 12:00PM

https://ift.tt/30tOTbI

Insurgents take on the scandal-hit Big Four - Financial Times

"four" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ZSDCx7

https://ift.tt/3fdGID3

No comments:

Post a Comment